By Stu Harrison

(Honduras "Elections" exposed) - Real Participation around 35%

People stayed away in droves. In a November 29 statement, the FNRG said: “You don't need glasses to see what is in front of your eyes.

“Nationwide monitoring by our organisation proved that the level of abstention during the process is at least 60-75%, which is the highest in our national history.”

This should come as no surprise. A Honduran polling company revealed in August only 17% of Hondurans supported the coup and most wanted Zelaya returned.

On the evening of the vote, the TSE released figures claiming that with 98% of the vote counted, abstention was only 38.14%. Right-wing National Party candidate Porfirio Lobo was declared the winner.

However, Congressperson Elvia Argentina Valle released a statement comparing the figures released by the TSE with the number of registered voters. She pointed out that if the TSE’s figures were right, abstention would be 62%.

The TSE was forced to acknowledge a “mistake” and said, in fact, little more than 50% of the votes had been counted. The TSE has since revised its participation figure down to 49%. Its blatant attempt to pretend it was much higher indicates the seriousness with which this claim should be taken.

On November 29, the FNRG said: “The Honduran people have punished the candidates of the coup and the dictatorship — all of who are going to have a very hard time trying to convince world public opinion that a high percentage of the people turned out to vote, when no such thing happened.”

The United Nations, European Union (EU) and the Organisation of American states did not send monitors to observe the vote, refusing to give the coup regime’s fraud election legitimacy.

After the vote, Zelaya said: “The election may have passed, but it’s the same military officials, the same Congress, the same people who worked against me still in power, so what does this fix?

"Absolutely nothing.”

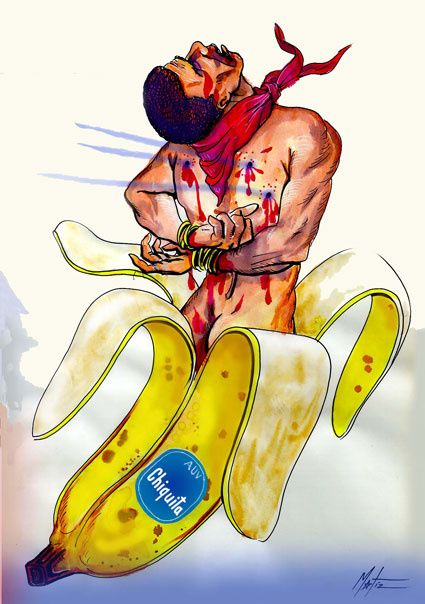

Elected in 2005, Zelaya upset corporate interests when he raised the minimum wage by 60% and joined the anti-imperialist political and trading bloc initiated by Venezuela and Cuba, the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas (ALBA).

Zelaya tried to hold a non-binding referendum intended to open the way for an elected constituent assembly to draft a new constitution. Early on the morning of the vote, the military stormed Zelaya’s residence, kidnapped him and exiled him to Costa Rica — still in his pyjamas.

This sparked a sustained mass uprising of the poor majority. Daily mass demonstrations, strikes, occupations and road blockades cost the impoverished Central American nation millions of dollars each day.

The popular resistance received a further boost when Zelaya secretly returned to Honduras in September and took refuge inside the Brazilian embassy, where he remains.

The coup regime responded to the resistance with growing brutality. Dozens have been killed or disappeared and thousands detained. The FNRG has condemned the revival of death squads tied to the military.

The repression increased in the lead-up to the vote, which took place under conditions of a state of siege.

But resistance has continued.

A protester told AFP on December 1: “We’re here to show the world and Honduras that the resistance continues. The election results were fixed.”

AFP said protesters rallied on post-election “with their fingers aloft to show they carried no ink mark [voters’ fingers are marked with ink]”.

Canadian trade unionist Tyler Shipley, in Honduran capital Tegucigalpa on election day, said o Candiandimensions.blogspot.com on the November 29: “In every place I went, people told me that this street or that street was usually packed with people, that election day is normally a huge event.

“That certainly wasn’t the case today.”

Rafael Alegria, from the farmers’ rights group Via Campesino, said on November 30: “[The regime was] raffling off home appliances such as fridges, and even houses, for those who voted in an attempt to get them into the booths.”

Large supermarkets also gave discounts and offers to anyone who could show ink on their fingers. The Catholic Church issued statements explaining that not voting was a mortal sin.

Repression continued on election day. Security forces used water cannons and tear gas to disperse a protest in San Pedro Sula. Beatings, arrests and one disappearance were reported.

A Reuters reporter and two human rights monitors from the Latin American Council of Churches were among the injured.

Javier Zuniga, the head of the Amnesty International delegation in Honduras, said: “Rights like the right to communicate and receive information, which are fundamental for an electoral process so that people have a perspective on what is happening, are constantly suffering limitations.”

Referring to reports of police violence and intimidation, Zuniga said: “Justice seems to have been absent also on election day in Honduras.”

None of this stopped the United States government, which has refused to cut off all aid and military ties to the coup regime, immediately welcoming the vote and pledging to recognise the new government.

Peru, Panama, Colombia, Costa Rica and El Salvador also indicated their willingness to recognise the vote and new government.

A key tactic of the coup regime was to use the elections to seek to ease its international isolation. Before the elections, no government or international institution had formally recognised the regime that overthrew Zelaya.

Director of the Centre for Families of the Disappeared and Detained of Honduras Bertha Oliva said on November 30: “They have put civilian clowns in office to put a clean face on the military coup.”

However, many governments and institutions are refusing to play along. In Latin America, Venezuela, Cuba, Brazil and Argentina, among others, indicated their refusal to do so. The EU has also said it does not recognise the vote as legitimate.

The regime stands more exposed than ever. The FNRG organised a “victory celebration” and protest march on November 30. It is clear the Honduran people will continue their struggle to defeat the coup regime and secure a constituent assembly — so the constitution that favours the elite can be democratically transformed to the benefit of the people.

(video added by Internationalnews)

Related stories:

http://www.greenleft.org.au/2009/821/42222

http://www.internationalnews.fr/article-honduras-big-poll-boycott-exposes-us-backed-regime-video-40710120.html

![Géopolitique : Union transatlantique, la grande menace, par Alain De Benoist [tribune libre] Géopolitique : Union transatlantique, la grande menace, par Alain De Benoist [tribune libre]](http://www.breizh-info.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/tafta.jpg)