WSWS

13 July 2009

A sharp exposé of US “humanitarian intervention” in the former Yugoslavia—but some false conclusions

By Charles Bogle and Paul Mitchell

Professor David N. Gibbs is to be commended for writing the first full-length academic exposé of the “widely accepted consensus” that the Western powers intervened reluctantly in the Yugoslav conflict of the 1990s.

In First Do No Harm: Humanitarian Intervention and the Destruction of Yugoslavia, Gibbs refutes as well the claim that the great powers acted only after pressure was exerted by former “anti-establishment” intellectuals, such as Samantha Power, Christopher Hitchens, Michael Ignatieff, and Todd Gitlin.

Power, for example, has written, “US policymakers did almost nothing to deter the crime [genocide in Yugoslavia]. Because America’s ‘national interests’ were not considered imperiled by mere genocide, senior US officials did not give genocide the moral attention it warranted.... The key question...is: Why does the United States stand so idly by?”

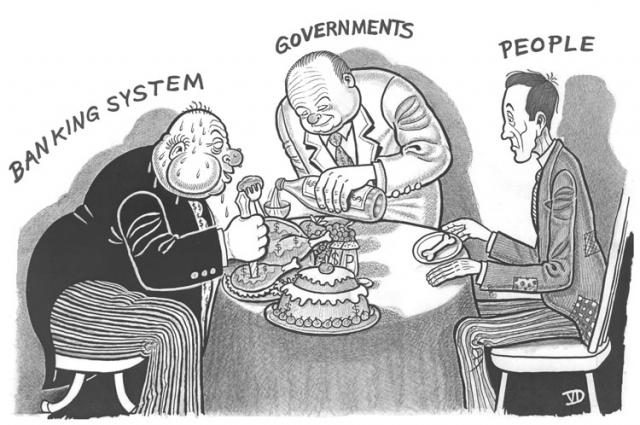

Gibbs, associate professor of political science at the University of Arizona, systematically debunks the notion that the Western powers were motivated primarily by humanitarian concerns, rather than “power politics,” and that human rights conditions were improved in the region as a result. He marshals a large body of evidence to support his thesis that so-called humanitarian intervention was a “classic act of power politics,” “perfectly consistent” with the geostrategic interests of the US and other key states, as well as “private interest groups” within those states.

The author outlines his quite correct “basic argument” that “during the post-Cold War period, the US was seeking to reaffirm and then strengthen its position of worldwide dominance.

“US policy makers resolved to take advantage of the new opportunities offered by the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991: They sought to use this circumstance to establish a new order of unilateral US hegemony with no challengers, and to perpetuate this dominance as far into the future as possible.”

This perspective found expression in the Pentagon’s 1992 Defense Planning Guidance (DPG), authored by then-Undersecretary of Defense for Policy Paul Wolfowitz and other neo-conservatives, outlining a policy of unilateralism and pre-emptive military action to prevent any other nation from rising to superpower status and thus threatening US access to oil and other resources. Many of the main elements of the DPG were incorporated into the US National Security Strategy, published in 2002 and known popularly as the “Bush Doctrine.”

Gibbs argues that a “closely related” US objective was to find a new role for the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO), considered “a key instrument of US hegemony.” However, this unilateralist US vision “collided” with the ambitions of the European Union (EU), particularly a newly “assertive” re-united Germany, which was seeking to become “a major international actor, independent of the US.”

Thus, Gibbs concludes, Yugoslavia became the “principal arena” in which the US and EU sought to “showcase” their “respective capabilities” and “power positions.”

He reminds his readers that it was Germany that first intervened in the Balkans region, not the US, which was still preoccupied with the collapse of the Soviet Union and Operation Desert Storm in Iraq. First Do No Harm presents new evidence revealing that the Germans encouraged Slovenia and Croatia, months before the civil war broke out, to secede from the Yugoslav federation.

The initial “quiescence” of Washington in the Balkans region, Professor Gibbs argues, was seen as a sign of weakness. But, he explains, the Republican administration of George H. W. Bush, contrary to the claims of most studies, began actively intervening in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where war broke out in April 1992. US officials encouraged Bosnian leaders such as Ilija Izetbegovic to secede, undermining the European-brokered Lisbon peace agreement and sparking off “one of the most visible and important conflicts of the post-1945 era.”

The Clinton administration, coming to power in January 1993, faced the same dilemma as its Republican predecessor—how to use the Yugoslav conflict to reaffirm US power and offset Europe’s quest for an independent role, without getting embroiled in a “Vietnam-style quagmire,” involving large numbers of ground troops. The US continued to block EU peace plans and supplied Bosnian Croat and Muslim forces with military equipment in a large-scale covert operation.

Clinton invoked Serbian human rights violations—going so far as to compare them to the Holocaust—to justify “Operation Storm,” involving 100,000 Croatian troops backed by aircraft and artillery against Serb targets in the fall of 1995, which resulted in “probably the largest single act of ethnic expulsion of the entire war,” Gibbs notes.

The Dayton Accords that ended the war, not substantially different in their content from the earlier EU-sponsored peace plans, Gibbs argues, allowed the US to put a diplomatic face on its actions. Even so, US dominance grew increasingly tenuous during the late 1990s, highlighted by the EU’s adoption of the euro as its official currency and the attempts by the European powers to establish an independent foreign and military policy. Once again, the US used Serb atrocities—this time against the American-backed Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA), which, Gibbs notes, committed their own share of horrors—to justify “humanitarian intervention” and launch a devastating bombing campaign against Serbia during the 1999 Kosovo war.

The author draws on new evidence, provided by former UK Defense Minister John Gilbert, to prove that the US-dictated peace terms at the Rambouillet Peace Conference in 1999 “forced [Yugoslav President] Slobodan Milosevic into a war” and provide a reason for American intervention.

The resulting exodus of approximately a quarter of a million people, or “disfavored groups,” satisfied the KLA’s desire to ethnically cleanse Kosovo, set a precedent for NATO going to war virtually at will, and once again established US dominance at the expense of the Europeans. According to Le Monde, the French bourgeois daily, the Kosovo war was widely considered “a European—and a United Nations—humiliation, as well as a success for NATO.”

In considering the domestic origins of the Yugoslav conflict, the author correctly exposes the claims made by writers on the right and “left” that the Serbs were solely responsible for the conflict and its consequences.

The Serbs, Gibbs explains, “were only one party to the breakup of Yugoslavia...other ethnic groups bear at least as much of the blame.” As for Milosevic, he was no better or worse than the other ex-Stalinist bureaucrats Franjo Tudjman in Croatia and Milan Kucan in Slovenia. The author observes correctly that each of these leaders rose to prominence due to the influence of the Western powers, which demanded structural adjustment policies, enforced by the IMF, resulting in a catastrophic decline in living standards, and making the population vulnerable to nationalist demagogy.

Gibbs asserts that “[t]he principal reason for the [Western] hostility toward Milosevic was that he advanced views and specific policies that were anticapitalist.” The author points out that Milosevic, a former favorite of the Western powers, used the Socialist Party as a vehicle for “his nationalism” at the same time that he used socialist and anti-capitalist phraseology to appeal to the masses and “hardline Communists” within the Yugoslav army.

At this point, Gibbs is politically at sea. Milosevic’s nationalism had nothing to do with “communism.”

In the 1980s, Washington looked upon Milosevic, a former head of Beobanka, one of Yugoslavia’s largest banks, and frequent visitor to Paris and New York, with favor to the extent that he cooperated with the IMF, initiated free market policies, and dismantled state industry in Yugoslavia.

Milosevic, however, defended the perspective of a federated Yugoslavia, because of Serbia’s dominant position within it, and saw the Western powers’ encouragement of national separatism as a threat to Serbian national interests. In 1988, for example, he helped initiate the so-called “Anti-Bureaucratic Revolution,” which blamed the 1974 Constitution for loosening Serbia’s control over its provinces (Kosovo, Montenegro, Vojvodina) and allowing other republics, primarily Slovenia and Croatia, to exploit Serbia’s natural resources.

Even in the aftermath of the Bosnian civil war, in 1995, the Western powers considered maintaining Milosevic as an ally in the Balkans. He became one of the prime guarantors of the Dayton Accords and worked closely with the US in its implementation. It was only when he resisted the further break-up of Serbia—due to America’s cultivation of the KLA—and rejected Washington’s demands during the Rambouillet talks that Milosevic was declared a war criminal.

Milosevic was targeted, not on account of his “anti-capitalism.” Like other former allies and “assets”—Saddam Hussein in Iraq, Bin Laden and the Taliban in Afghanistan—he had outlived his usefulness. The Serb leader had become an impediment to American plans for the Balkans, a strategic part of the Eurasian continent within striking distance of Russia, the former Soviet republics, the Middle East and the Caspian Sea—regions rich in oil, gas and other critical natural resources.

While Gibbs’s book is quite valuable in its presentation of the history and nature of Western intervention in Yugoslavia, it suffers from certain methodological limitations. Though he discusses the social interests that actually motivate US policy—the motives that lie behind the rhetoric—a class analysis is not systematically worked through.

This comes out at the conclusion of the book, where the author calls for a new non-interventionist US foreign policy based on the criterion of “Do No Harm.” He states that advocates of “humanitarian intervention” should be asked to answer certain conditions, including demonstrating that the intervention will do more good than harm. This lends too much credibility to the proponents of “humanitarian intervention” in the political establishment, which his book is devoted to debunking.

Gibbs’s book demonstrates that Republican and Democratic administrations have followed virtually identical foreign policies, based on economic and geostrategic interests. It is not a question of conditioning humanitarian intervention, but exposing the real class interests that motivate US policy.

The coming to power of Barack Obama, as the expansion of the bloody war in Afghanistan and Pakistan and the political intervention in Iran demonstrate, is seen as an opportunity by powerful sections of the US ruling elite to continue the pursuit of global hegemony by somewhat more tactically agile means.

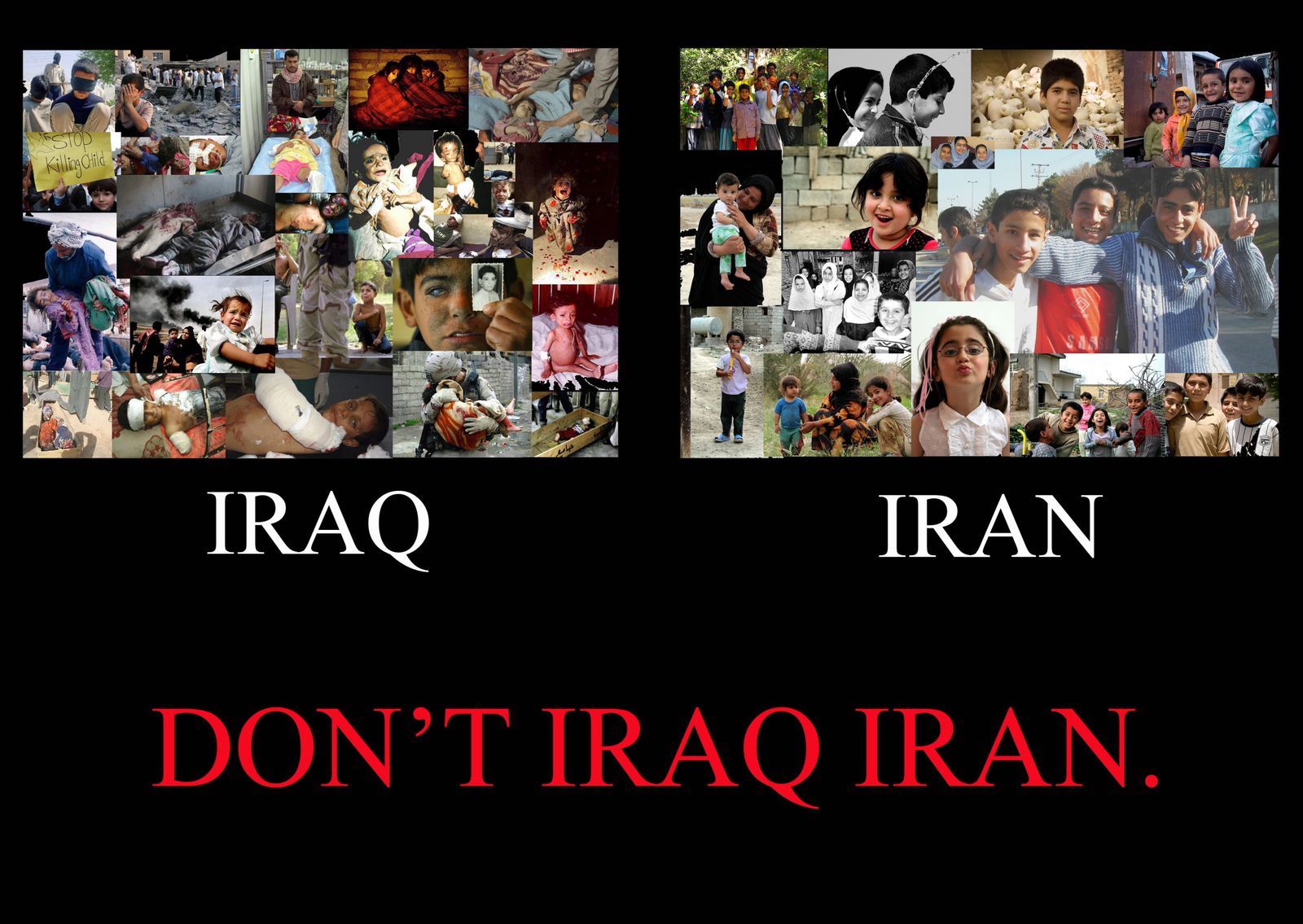

The eruption of US militarism was and remains an objective socio-historical process, the product, above all, of the historic decline of American capitalism and an attempt to counteract this decline through force of arms. It signals a new era of colonial-style wars of conquest and inter-imperialist rivalries that are bringing terrible suffering and which ultimately threaten the very survival of humanity.

Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press, 2009

The authors also recommend:

What does Milosevic’s downfall portend?

[7 October 2000]

Marxism, Opportunism and the Balkan Crisis

[7 May 1994]

Our Emphasis.

http://www.wsws.org/articles/2009/jul2009/book-j13.shtml

![Géopolitique : Union transatlantique, la grande menace, par Alain De Benoist [tribune libre] Géopolitique : Union transatlantique, la grande menace, par Alain De Benoist [tribune libre]](http://www.breizh-info.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/tafta.jpg)